Medical research can be powerful — and so are the women who make it happen. One of these is Ruchi Gupta, MD, who is doing some amazing work in food allergy research, empowering communities with data-driven results that can change lives for the better.

I first met Ruchi Gupta, MD, MPH, at a conference held by her team at the Science & Outcomes of Allergy & Asthma Research (SOAAR) program in the Center for Food Allergy & Asthma Research (CFAAR) at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. The SOAAR team aims to find answers and shape policies surrounding pediatric and adult food allergy and asthma. She also is the director of the Center for Food Allergy and Asthma Research (CFAAR) in Northwestern’s Institute for Public Health and Medicine.

Ruchi, a professor of pediatrics and medicine at Northwestern, is also an attending physician at Ann & Robert H. Lurie’s Children’s Hospital, where she conducts clinical, epidemiological, and community-based research, most notably in food allergy, especially its prevalence in kids, and asthma epidemiology. Among her more than 100 publications is The Food Allergy Experience.

I can’t remember who said it to me, but one of my favorites (words of wisdom) is, “Nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care.” That’s the one I live by.

In other words, she is the real-deal expert, and she is generous about sharing her knowledge and inspiring a passion to create a better world for those with food allergies. She jumps at the opportunity to mentor others, from high school students and undergrads to medical students, residents, fellows, and junior faculty.

And now us —I felt so grateful when she agreed to sit down with me to chat about her experiences as a woman leader in this field.

In what ways does your research in food allergy empower communities to be more accommodating?

One of our pillars at the Center for Food Allergy & Asthma Research is community, so I have been focused since day one to better understand the issues real people with food allergies have and how can we make their day-to-day life better as we wait for the treatments to be developed.

One area we focus on is policies schools have for kids with food allergy. There was almost nothing when I first started, and it’s been amazing to see is all the policies that have come into play. Chicago was one of the first large public-school systems to stock epinephrine, though that only happened after a girl with a peanut allergy died after eating food that was supposedly peanut-free. While the reason for the change was not the greatest, at least everyone came together after and vowed to never let something like that happen again. That effort in the Chicago public schools since have been cited in the development of policies across the country. That feels really good.

We always ask, what can we do that will have an impact on children and adults every day? How can these policies be developed, and then how can people be trained?

An early childhood teacher recently came to me and said, “This is great, but you don’t have anything for childcare centers.” So we’re working on building that. Then I had someone else come to me and say, “This is all great, but you don’t have anything for colleges.” So we’re working on that. We had people say they’re noticing there are more adult-onset allergies. I’m a pediatrician, but I could adapt the survey I used for childhood research to get a better understanding of that.

We listen very closely to the community to find out which issues are important to them, and then do research around those issues so we can get the data out that’s needed to make change happen. We’re developing a community board to help guide us on what should we focus our time and energy in the center on doing research on to help the community.

I’ll stop here, but this definitely is one of the most important missions of my own career and the center.

What’s the biggest obstacle you have faced with your research and everything else you do in your work?

I would say one of the biggest obstacles is time. By the time I got my medical degree, did my pediatric residency and fellowship, I was in my 30s. And then to do research, you have to apply for grants to get funding, which takes a lot of long nights and a lot of effort in addition to doing all your clinical duties. A big challenge for a lot of women is that, just when all of that is happening, you’re also thinking about starting a family. That is a lot to juggle.

I’ve seen a lot of women who have a great gift for research decide to do more clinical work instead of dealing with getting grants to pay for themselves and their staff to do the research. You’re always chasing grants, and a lot of the ideas that you are really passionate about may not get funded. You sometimes question if it’s worth it. I love clinical, I love seeing kids — is that okay to stay there or do I keep pushing on to try to make this research happen?

But if I stay with just doing clinical, I can only help one at a time. Research for me is a way to have a bigger impact.

My biggest message from this obstacle is there’s a lot of guilt. You’re not going to be able to do everything perfectly all the time. But if you keep going, you will get a grant, which will lead to another grant. There is light at the end of the tunnel.

What’s about your work gives you the greatest joy?

My greatest joy is mentoring and supporting young people to help them live their dream. We have this amazing high school program where we work with the Chicago Public School System and it is so rewarding to see young people become empowered and believe in themselves.

Research sounds scary, but it can be simple. It could be finding an issue in your community, thinking about facilitators and barriers, thinking up a small solution that might make it better, and testing it. It doesn’t have to be a mass-scale thing. It is so empowering and my biggest joy to see young people learn they can have an impact by doing even a minor research project and showing success.

What words of wisdom has your mother, your grandmother, aunt or another woman in the industry shared with you that has resonated and helped guide your career and your life?

I can’t remember who said it to me, but one of my favorites is, “Nobody cares how much you know until they know how much you care.” That’s the one I live by.

When I was young, there were times when it was all about the grades and scores, and I always felt I had to work harder than others. I would study a lot and still not do as well as some who said they studied very little. I had to learn is not to let scores and grades be my defining factor. Everybody has to work hard, and we all have gifts. But you will only get as far as you want if your intentions and your goal are pure.

I would like to be remembered as someone who made a difference in people’s lives through the work I do, but also as someone who helps develop other people to continue to make a difference.

Another thing I learned young and that I continue to tell my team is to know our true goal is to make a positive change in the world. Whenever we think of any project or any new study, we have to consider if we really think it’s going to make positive change in the world. And if it will, then we should move forward.

How do you define food inclusion?

Food inclusion is making sure that every person has what they need, whatever food-related conditions they may have. When people don’t feel included, they stay away from social situations because they’re embarrassed or they don’t want to bring up their food condition. And so how can we work together to make sure that that’s not an obstacle, that everybody can feel as included?

I don’t think the exclusion is purposeful a lot of times. I think it’s mainly due to a lack of awareness and understanding.

How do you want to be remembered in history for what you do?

I would like to be remembered as someone who made a difference in people’s lives through the work I do, but also as someone who helps develop other people to continue to make a difference. That comes back to the mentoring — we can only do so much alone. But if each of us helps another 10 or 100 people to believe in themselves and develop their ideas and their dreams, then our impact is multiplied so many-fold.

As a female in the medical field, what advice would you give new female medical students?

I would recommend that they look at all their options. There are so many career paths to take — keep learning, find female and male mentors, and keep your options open.

I got into food allergy research because of a family I met. I wasn’t necessarily passionate about it at first, but their passion about trying to make a difference for their kids and others with food allergy was really infectious. And when I started looking into it, I realized it was an area that was lacking and I could use my skill set to make a difference in their lives and the lives of other families.

And don’t stop being open to new opportunities. I’m not done! I just keep doing what I love and watch for new doors to open that will help me continue to do what I love.

If you could have anyone invite anyone over for dinner in the world, who would you invite and why?

I would say Oprah Winfrey. I really respect her. She is an incredible woman who does so much good, who supports so many people and helps pull other people up. She’s just such a force.

How to Find Dr. Gupta

Website — Team SOAAR

Facebook — Team SOAAR

Instagram — Team SOAAR

Twitter — SOAAR4Research

LinkedIn — Ruchi Gupta, M.D.

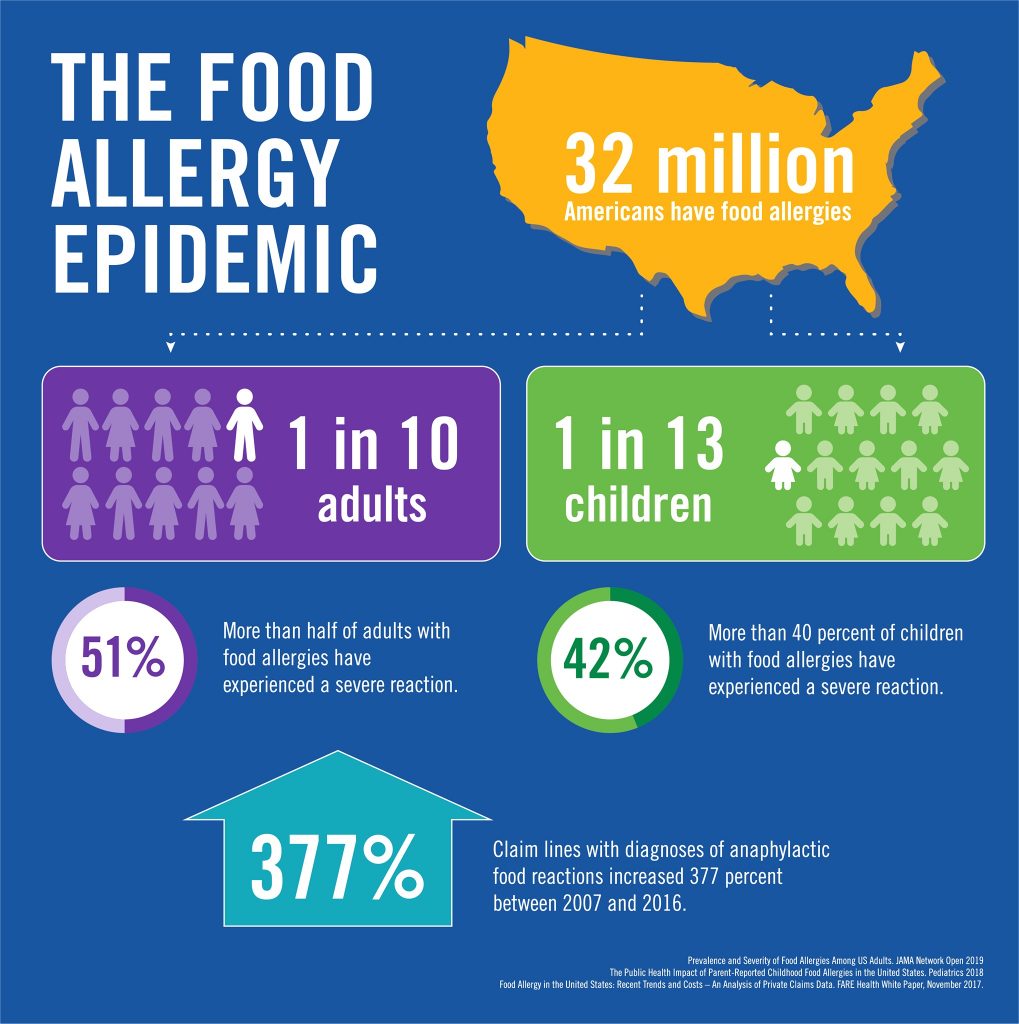

Prevalence, Severity and Distribution of Food Allergy in the United States