Attorney Mary Vargas is a fierce fighter for the civil rights of people living with food allergies, celiac disease, and non-celiac gluten sensitivities.

Continuing this month’s celebration of amazing women in food and beverage, I’d like to introduce you to Mary C. Vargas. Mary is a founding partner with Stein & Vargas LLP, a civil rights law firm committed to the principle that all people have full and equal access to all parts of American society. Her firm handles both litigation and advocacy on behalf of individuals with disabilities, including those with food allergies, celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity.

How did you get started in your work in the food allergy world?

I started out as a disability rights attorney litigating on behalf of people who are deaf and hard of hearing. Then I had my kids — I have three boys, and my youngest has food allergies and celiac disease. He was trying to do the same things his brothers had done, such as go to the same summer camps, but he started running into barriers. I had to pave the way for him, relying on my disability rights background as well as my food-allergy-mom skills. And I realized that that I was really doing the same work that I had always done, only this time it was about food allergy.

While it’s scary when they’re in preschool, younger kids also are easier to contain. As they get older, they’re supposed to get more independent and do all the things that other kids do. That’s when it’s even more important that kids like my son be able to advocate for themselves when their food allergy and celiac disease means they may need more or different support than other kids.

What has been your greatest obstacle?

People who know their biases and admit to them out loud are one thing, but it’s the people who say they’re not biased, those who say they have your back, who can be the most dangerous. Sometimes your own community can send friendly fire.

While there is amazing support in the food allergy and celiac community, there also are some folks in that community who say, “I would never let my child do that,” or “I would never file a lawsuit for this — people aren’t going to want to serve us anymore.”

This is an especially difficult barrier when selecting a jury — if they won’t say their bias out loud, you have no ability to address it head on and change their minds.

Another challenge is the person who doesn’t recognize what they don’t know. For example, when you have a chef who runs a kitchen and thinks he knows what gluten is, and then testifies that gluten can be burned off in hot oil. How do you ever change that if that person can’t see the risk that they’re creating for a person with celiac disease, especially since that person has been promised that they can eat safely? And how do people with these dietary restrictions know when somebody they’re relying on is worthy of their trust?

What in your professional work makes you optimistic?

I recently presented at a training program for folks who provide dining services at colleges and universities, and what struck me was that there were people in the room who just got it. One person asked a question about how to serve students safely without stigmatizing them. She was worried about wrapping and labeling the food, which makes it looks so different from everybody else’s.

The fact that there are people in this industry, with all of its demands, who are thinking about the human side of it, the social and emotional impact of what they do, is really helpful to me.

What has been your experience as a woman in your professional life?

Even now it’s still unusual in the legal profession for there to be women on both sides in courts. Once, about two years ago, I went to a mediation and there was a moment where we all kind of stopped and realized that we were all women there: a woman mediator, a woman defense attorney, myself and my female co-counsel, and our client who was also a professional woman.

And the fact that only two years ago we all sort of had this communal moment of “this doesn’t happen” says a lot. The reality is, in my cases, almost all the time, the attorney on the other side is still a man

What words of wisdom have women in your life shared with you?

My grandmother is a hero to me. Whatever problem I brought to her, she always told me, “I’ve got broad shoulders.” She was this little tiny woman who had anything but broad shoulders physically, but I still lean on her when I don’t have the answers with my own kids or I don’t know how to do something in my practice. I hear her voice saying, “I’ve got broad shoulders,” and it propels me forward.

What do you most appreciate about what you do?

My work enables me to give a voice to people who aren’t being heard, such as a college student who could never afford a $685-an-hour attorney to speak for them. I’m not a person who could get up a day, every day and happily do a job that didn’t feel was changing the world in some way. The work feels powerful and motivating — I love that.

I also love that I don’t know the answers. We’re still building legal precedent in the area of food allergy.

And I have incredible opportunities to get to work with attorneys and clients throughout the United States. It’s a neat thing to be able to talk from my home office to somebody in Washington state or Nevada who’s having a challenge and consider whether there’s something we can do to help them. And very often those people become a part of us at Stein & Vargas — I feel very grateful that I have clients and colleagues who value the work that we do on a human level. That’s awesome.

I also can work from home, which allows me the flexibility to answer the phone call from the school when my child is having health issues.

In what ways is the power of food being used to empower communities and connect people to each other?

When I was working at the National Association of the Deaf, we represented people who were denied access to all kinds of places because of their disability. And I remember focusing on things that I thought were important, like access to hospitals and jobs. Then association members said, “That’s great, but what matters to us is having the right to live in the world, in the social realm.”

So when we’re looking at cases, we very deliberately focus on access in dining, because that is important in every area, from hospitals to universities to restaurants — everywhere.

It’s really important to for all of us to make sure that we’re amplifying the voices of the people who are living with disabilities and that we’re making space for their experience and that we’re supporting and including them where possible. We need to recognize what we don’t know — there are all kinds of ways that we all fall short — and being willing be more inclusive, because that benefits everyone.

If you’re at a conference and you are not able to participate fully and seamlessly and without humiliation with everybody else at a luncheon, you’re not in the place where the most important work of a conference happens. Yes, presentations are great, but where the connections are made, where the networking happens and where a lot of the learning is forged is in the informal spaces, and so much of that revolves around food. It is important to be able to participate fully in the spaces where the important stuff happens.

This is particularly important when it comes to how kids think about themselves and their role in the world. When kids with dietary restrictions on field trips are forced to eat outside instead of in the restaurant with everyone else, it’s teaching them at a very young age that they don’t belong, that they’re less than, that they’re not welcome — all kinds of messages that we don’t want to send.

At the same time it’s teaching the rest of the children that it’s okay to exclude someone, not that that person is a part of the community and has something valuable to offer that will enrich the community if they’re allowed to be a part of it.

It’s really important to for all of us to make sure that we’re amplifying the voices of the people who are living with disabilities and that we’re making space for their experience and that we’re supporting and including them where possible. We need to recognize what we don’t know — there are all kinds of ways that we all fall short — and being willing be more inclusive, because that benefits everyone.

If you could invite anyone to dinner, who would you invite?

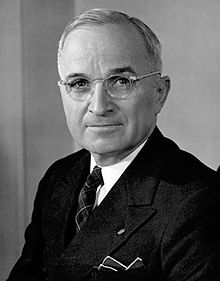

Probably Harry Truman. He was humble. He failed a lot and he kept going, and he valued his family.

Probably Harry Truman. He was humble. He failed a lot and he kept going, and he valued his family.

He’s particularly near and dear to my heart because I got to go to law school because of him. Instead of building a stone memorial like we’ve done for many other presidents, a living memorial was established, a scholarship program that funds students who want to do public interest work. I received a Truman scholarship. It helped pay for my law school education, but more importantly, it gave me the courage to go to law school in the first place.